Vietnam and the Anti-War Movement

1968 would mark a terrible shift in America’s war in Vietnam proving to be the conflict’s bloodiest year. On January 30, the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese People’s Army of Vietnam launched a series of surprise attacks on American and South Vietnamese forces in what would become known as the ‘Tet Offensive’. The conflict was exacerbated by American escalation – U.S. President Lydon B. Johnson approved an increase in US troops to a maximum of over half a million combatants. The death toll for the North Vietnamese in 1968 would exceed the number of American fatalities throughout the entire war. Although the Tet Offensive was technically a loss for the North, it demonstrated the vulnerability of South Vietnam. The inevitability of stalemate, if not defeat, exacerbated the pressure of the anti-war movement on the American home-front. By 1968, the US military effort was clearly failing and the anti-war protestors were forcefully making their voices heard.

Bertrand Russell, of course, was years ahead on the anti-war trend. At one time imprisoned for his conscientious objection to the First World War, he again emerged as an unlikely figurehead of the 1960s anti-war movement. As early as 1963, he wrote a letter to the New York Times condemning the U.S. for “conducting a war of annihilation in Vietnam” and criticized the use of napalm as a weapon of war.

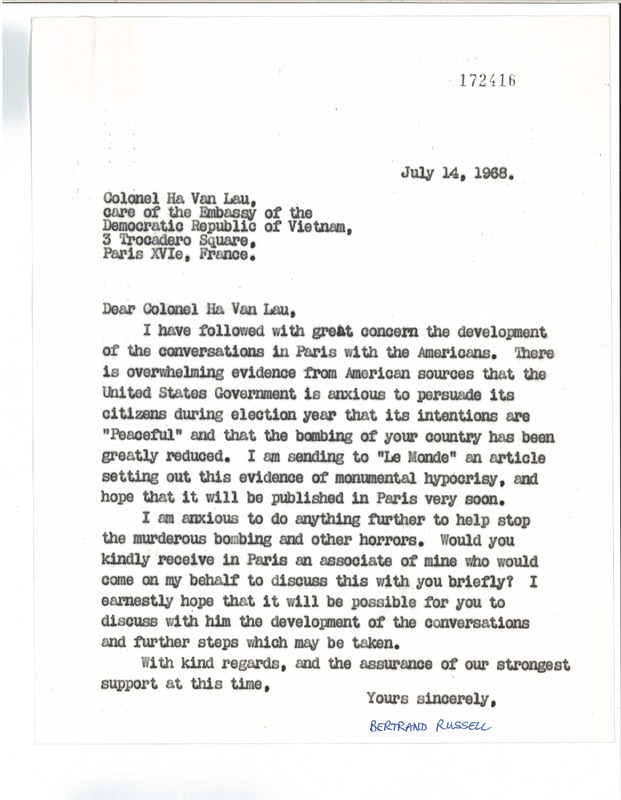

Just as he had exchanged telegrams with both Kennedy and Khrushchev during the darkest days of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Russell kept correspondence with North Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh and the South Vietnamese military. On February 1st 1965, he cabled General Khanh in Saigon, South Vietnam, and demanded an end to executions of demonstrators. Throughout the war, Russell maintained his public persona as an increasingly fierce critic of the war, publishing articles, and speaking out publicly against American cruelty and British complicity. Anti-war activism was the principal catalyst for the founding of the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation. In 1963, the foundation was tasked with “further[ing] the cause of peace, and to assist in the pursuit of freedom and justice, [to] identify and counter the causes of violence, and to identify and oppose the obstacles to worldwide community” (BRPF).

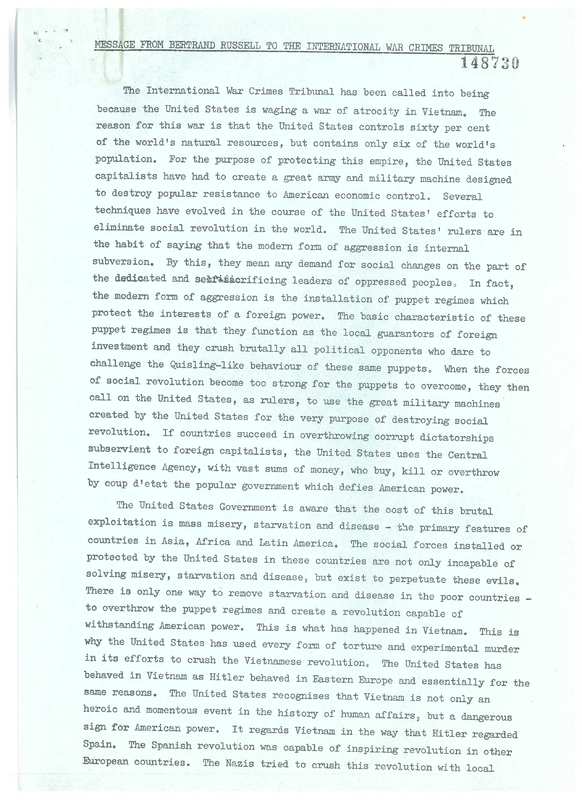

Russell’s anti-war work came to a dramatic climax in 1967 during the International War Crimes Tribunal, a citizen-led adjudication of America’s actions in Vietnam. Beginning in the summer of 1966, Russell wrote to a number of preeminent people around the world with an invitation to join a panel to investigate war crimes in Vietnam. The French existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, who Russell described as someone who’s courage he greatly admired “despite [their] differences on philosophical questions”, would preside over the proceedings. Other notable luminaries included the philosopher Simone de Beauvoir, the Yugoslav writer Vladimir Dedijer, and the political writer Isaac Deutscher. “I invited only people whose integrity was beyond question”, Russell would later write. The Tribunal was constituted in November 1966 and conducted two sessions the following year in Stockholm and Copenhagen. The Tribunal conducted interviews in a public trial to investigate the following questions:

Has the United States Government (and the Governments of Australia, New Zealand and South Korea) committed acts of aggression according to international law?

Has the American army made use of or experimented with new weapons or weapons forbidden by the laws of war?

Has there been bombardment of targets of a purely civilian character, for example hospitals, schools, sanatoria, dams, etc., and on what scale has this occurred?

Have Vietnamese prisoners been subjected to inhuman treatment forbidden by the laws of war and, in particular, to torture or mutilation? Have there been unjustified reprisals against the civilian population, in particular, execution of hostages?

Have forced labour camps been created, has there been deportation of the population or other acts tending to the extermination of the population and which can be characterised juridically as acts of genocide?

The Tribunal and its verdict would prove highly controversial. Russell himself would be accused of anti-Americanism in his overzealous interpretation of international law. Yet, history has favoured the spirit of the tribunal, if not its specific conclusions. Following a thorough investigation, evidence of atrocities and systematic acts of violence and aggression committed by the US against Vietnamese civilians brought the tribunal to a conclusion with a unanimous verdict of American guilt. This non-legally binding verdict would give inspiration to the anti-war movement and provide a basis for anti-war activism against future conflicts up to the present. The IWCT’s goal was not to exact punishment, but rather to ‘rouse the consciousness of the world’, and in that regard, it was a clear success. The Tribunal, with Russell at its centre, publicly accused the United States of war crimes (including the crime of genocide against the Vietnamese people), effectively making Russell persona non-grata in the US.

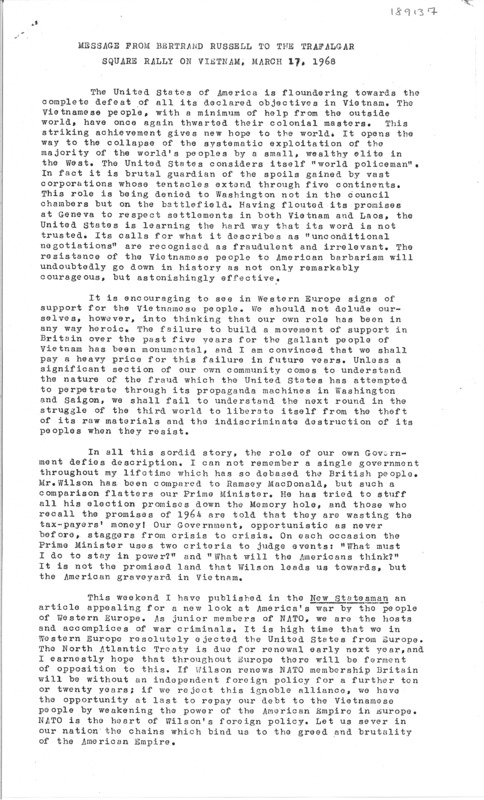

When the Tet Offensive arrived in 1968, Russell continued his clarion calls for peace and justice in Vietnam. At a massive peace demonstration in Trafalgar Square on March 17th, 1968, Russell sent a message which was read alongside other anti-war demonstrators including Vanessa Redgrave and Tariq Ali. (Ali, who had a long career as a public intellectual and New Left activist, first rose to international prominence as a witness at the IWCT.) The crowd of demonstrators marched through London’s streets to the U.S. Embassy in Grosvenor Square. A crowd of approximately 10,000 (not including Russell or the other speakers from the initial assembly) were confronted by policemen and the ensuing violence left dozens injured and many protestors charged. "The Battle for Grosvenor Square” would be forever remembered as an important moment in the history of British protest movements.

The Civil Rights Movement

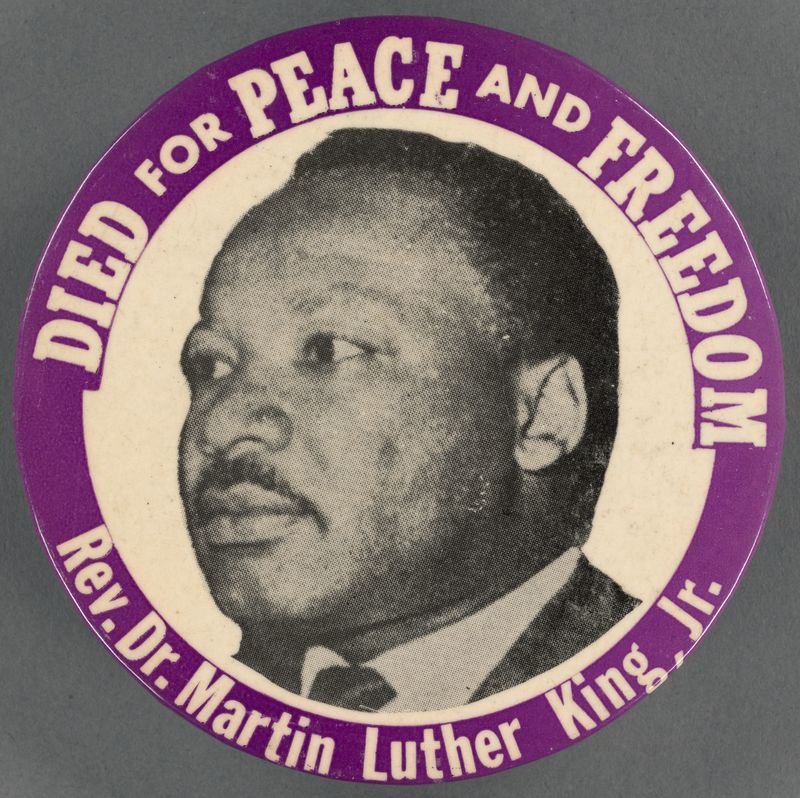

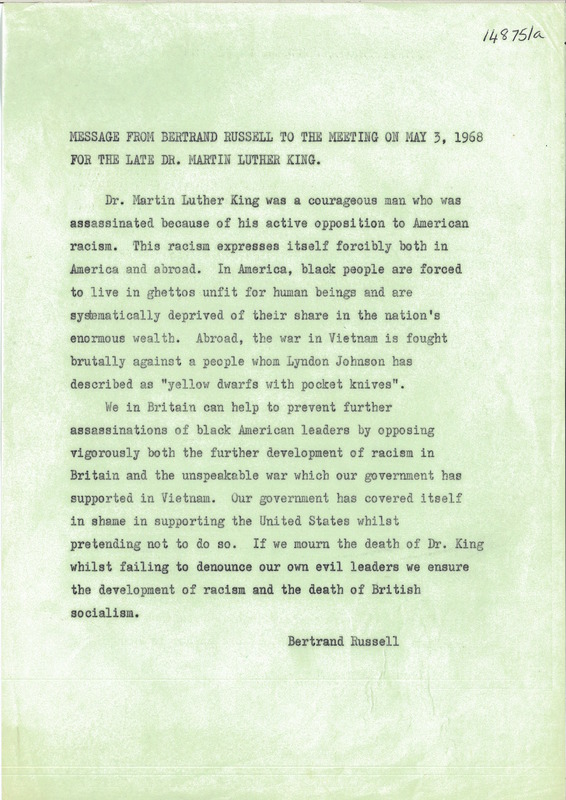

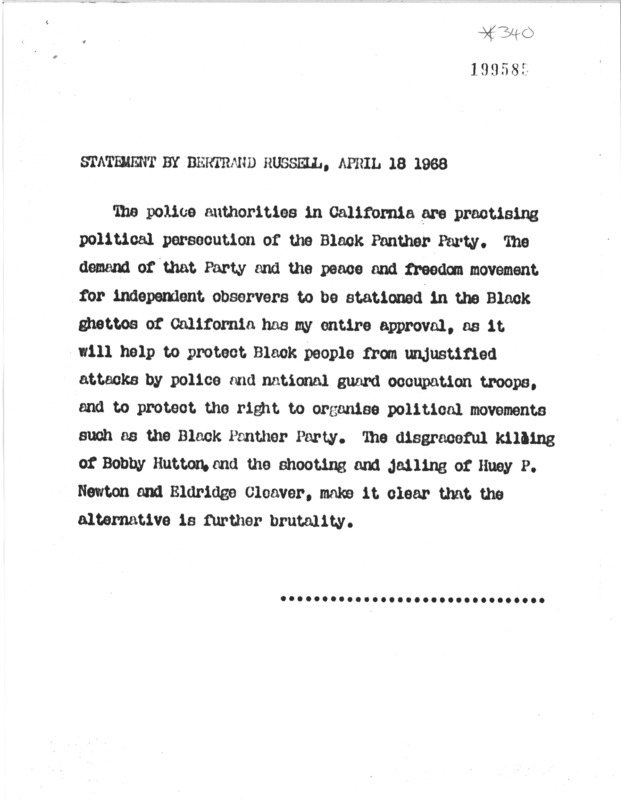

1968 was also the year in which Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. Russell and Dr. King maintained a correspondence, with the former writing in April 1965 that he “wholeheartedly support[ed]” the economic boycott of Alabama as a protest against Black American voter suppression (95905). At the time of his death, Russell issued two statements, one public and another private. The public statement was critical of Dr. King’s lack of radicalism, stating “Dr. King’s personal courage was remarkable, but many black Americans will conclude that his moderation was ineffective against a structure built upon vicious racism” (133756). In contrast, when asked to give a message to the London-based Colonial Freedom Movement, which held a memorial to Dr. King on May 3rd, his words were more magnanimous, drawing attention to how the British mourned the loss of Dr. King yet failed to challenge its own leaders for their complicity in America’s war in Vietnam. Russell stood firmly on the radical wing of the civil rights movement, as indicated by his support of the Black Panther Party and spoke out against their political persecution by police authorities and the CIA.

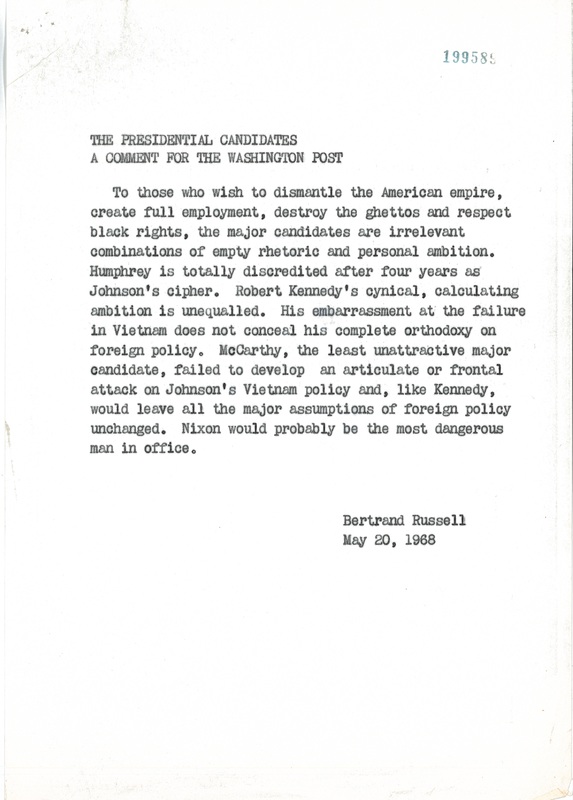

As an election year, ‘68 was tumultuous as it witnessed the election of a president who would come to embody the antipathy of the American Left: Richard Nixon. Months prior to the famous riots at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, the Washington Post had asked Russell for his opinion on the various candidates. His pithy reply, that they were all “irrelevant combinations of empty rhetoric and personal ambition”, ended with the remark that the eventual winner, Nixon, “was the most dangerous of them all”.

Bibliography

- Hanson, Victor Davis. “The Meaning of Tet.” In The Vietnam War, London?: Routledge, 2006.

- Feinberg, Barry., Ronald. Kasrils, eds. Bertrand Russell’s America, Vol 2. Boston: South End Press, 1983.

- LaFeber, Walter. The Deadly Bet

- MacIntyre, Donald. “My Part in the Anti-war Demo That Changed Protest For Ever”. The Guardian, 11 March 2018.

- Russell, Bertrand. Autobiography. 3 vols. London: Allen & Unwin, 1967-69..

- Russell, Bertrand. War Crimes in Vietnam. New York, N.Y: Monthly Review Press, 1967.

- Zunino, Marcos. “Subversive Justice: The Russell Vietnam War Crimes Tribunal and Transitional Justice

.”. The International Journal of Transitional Justice 10, no. 2 (2016): 211–29.

![War Crimes in Vietnam [cover]](https://expo.mcmaster.ca/files/large/540375d9b73cf805545f692358f2222cb3d61912.jpg)