Constantia et Labore: Celebrating a century of excellence at the Plantin-Moretus Press, 1555-1652

Four hundred and seventy years ago, Christophe Plantin established his printing press in Antwerp, a dynamic centre of commerce and culture. Plantin had trained as a bookbinder in France before moving to the Low Countries with his wife Jeanne Rivière. Together with their five daughters — Margareta, Martina, Catharina, Magdalena, and Henrica — they founded one of the most enduring and successful printing dynasties of early modern Europe. Other eminent printers, such as Franciscus Raphelengius and Jan Moretus, married into the family; their contributions became part of the Plantin story.

The William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections is honoured to hold more than fifty volumes produced by the Plantin-Moretus Press, including the monumental Antwerp Polyglot (1568-73), which was featured in The Great Sea exhibition at the McMaster Museum of Art in the summer of 2025. Here, you will find twenty-three works ranging in dates from 1555 to 1652. They showcase some of the subject areas in which the Plantin-Moretus Press specialised — including religious works, botanicals, travel narratives, philosophical texts, books on military history, and classics of Greek and Roman antiquity. From its inception, the Plantin-Moretus Press embodied the highest standards of bookmaking, typographical excellence, and elegant mis-en-page, with fine illustrations executed by the most talented artists and engravers of the day.

As you peruse this exhibit, we invite you to reflect on Plantin’s motto — labore et constantia. We celebrate the labour and perseverance of the many individuals who created these books, and of those who owned and cared for them during the intervening centuries.

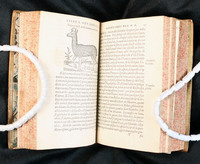

Pierre Belon. Les observations de plusieurs singularitez ... en Grèce, Asie, Indée, Egypte, Arabie ... (Antwerp, 1555). This edition of the Frenchman Pierre Belon’s travels in the Ottoman Empire was published in the same year that Plantin established his printing press in Antwerp. The book includes 45 woodcuts depicting plants, animals, maps, and people of the region, along with a portrait of the author. Many of the woodcuts, including this illustration of a chamois goat-antelope, bear the “A” monogram of the woodcutter Arnold Nicolai.

Biblia, ad vetustissima exemplaria castigata. (Antwerp, 1567). Plantin printed this octavo-format Bible in incredibly small “nonpareille” type. According to the bibliographer Léon Voet, who conducted extensive research in the Plantin-Moretus archives, a total of 1,250 copies of the octavo Bible were produced. This copy bears a contemporary gold-tooled limp parchment binding, with gilt edges and cover extensions. If you look closely, you’ll also see remnants of paired alum-tawed ties that would have been tied in a knot or bow across the edges of the book.

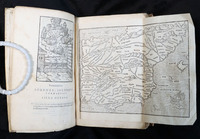

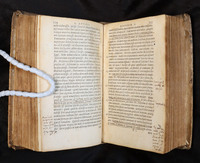

Gaius Julius Caesar. C. Iulii Caesaris Commentarii. (Antwerp, 1570). This edition of Caesar’s Commentarii is accompanied by printed annotations and Fragmenta of the Italian humanist Fulvio Orsini. The book includes woodcut illustrations by Cornelis Muller and woodcut maps by Guillaume van Parijs. This copy bears a contemporary limp parchment binding lined with parchment and paper waste bearing manuscript text in Latin and Greek. A sixteenth-century reader has neatly inscribed a summary of the first book in the outer margin of the first page.

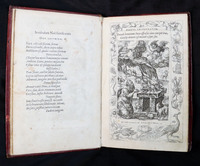

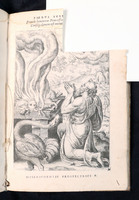

Benito Arias Montano. Humanae salutis monumenta. (Antwerp, 1571). While working on the Polyglot Bible, Spanish priest and scholar Benito Arias Montano spent his spare time composing spiritual poems. In the resulting emblem book, his poems are complemented by exquisite copper engravings and decorative borders by some of the finest artists and engravers of the day. This plate of Noah sacrificing a ram was engraved after a drawing by Petrus van der Borcht. The border, engraved by Jan Sadeler I (I.S.D.), was printed separately from the plate and the text.

Benito Arias Montano. Humanae salutis monumenta. (Antwerp, “1571” = 1583). The publishing history of Arias Montano’s devotional emblem book is complex. In this, the later quarto edition, the illustrations were redone in a larger format by different artists including Crispin van den Broeck. Arias Montano was ambivalent towards the result, which departed in style from early editions. Later readers of this copy excised and censored many of the illustrations. In this unsigned plate of Noah, for example, the bare-breasted angel in the upper corner has been cut out.

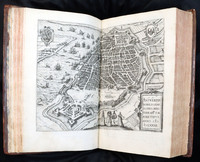

Lodovico Guicciardini. Description de touts les Pais-Bas… (Antwerp, 1582). This profusely illustrated contemporary description of the Low Countries, translated from the Italian, was first published in 1567 at the height of Antwerp’s Golden Age. Fittingly, the caption for this magnificent two-page view of Antwerp describes the city as the “noblest and most beautiful emporium.” In 2024, McMaster conservator Bronwen Glover repaired the binding and removed and stabilized pieces of parchment manuscript waste bearing text from Psalm 115.

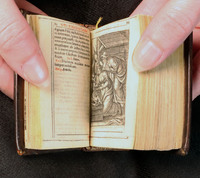

Officium beatae Mariae Virginis. (Antwerp: 1596). After Plantin’s death in 1589, the press was operated by his widow Jeanne Rivière and Jan I Moretus, who was married to Martina, Christophe and Jeanne’s second daughter. Religious and liturgical works, such as this diminutive Latin book of hours, formed the core of the press’s business under Jan I Moretus. The tiny copper-engraved illustrations were printed by a woman — Lynken van Lanckvelt, whose mother Mynken Liefrinck also worked as a printer. This is the only surviving copy of an edition of 3000.

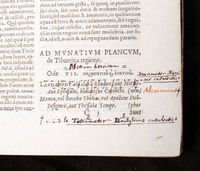

Horace. Q. Horatius Flaccus : cum commentariis … (Leiden, 1597). The erudite scholar and polyglot Franciscus Raphelengius worked as a proofreader for Christophe Plantin. In 1565, he married the printer’s daughter Margareta. Later in life, Raphelengius managed the Plantin Press’s office in the university town of Leiden. This edition of the Roman poet Horace features a mass of printed commentary surrounding the poems. In addition, a former owner has carefully annotated each poem by hand with marks of scansion, or poetic metre.

Aratus; Hugo Grotius. Hug. Grotii Batavi Syntagma Arateorum. (Leiden, 1600). Hugo Grotius — scholar, lawyer, diplomat, and polymath — acquired an illuminated ninth-century manuscript of Aratus, the Greek didactic poet whose Phaenomena describes constellations and celestial phenomena. Grotius turned to Christophe Raphelengius, who shared his Protestant sympathies, to publish a printed edition of the manuscript. The resulting book is lavishly illustrated with copper engravings by Jacob de Gheyn, including this image of the constellation Orion.

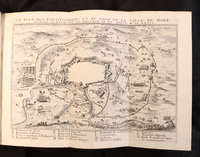

Jean Boyvin. Le siège de la ville de Dole, capitale de la Franche-Comté. (Antwerp, 1638). This volume is a sammelband of two works recounting battles and sieges that took place in the Franche-Comté region during the Thirty Years War. The siege of the Protestant-led city of Dole by the forces of Philip II of Spain took place in 1636. A fold-out copper-engraved map of the city is included as frontispiece to the first work in the volume, along with a title page engraved by Cornelis Galle, whose father Philips Galle was a publisher and engraver in Antwerp and whose siblings Theodoor, Philips II, Justa, and Catharina were all active as artists.

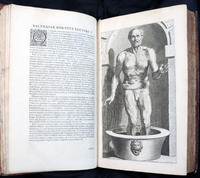

Seneca. Opera quae exstant Omnia : a Iusto Lipsio Emendata. (Antwerp, 1652). Balthasar I Moretus first published the works of Seneca edited by Justus Lipsius in 1632. His nephew and godson Balthasar II Moretus (1615-1674) published this, the fourth edition, twenty years later. The large copper engraving of the death of the Stoic philosopher is signed by the engraver Cornelis Galle and adapted from a painting by the artist Peter Paul Rubens. It flanks Moretus’s to the reader, in which he praises the wisdom of the editor Lipsius and the elegance of the artist Rubens.

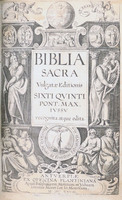

Biblia sacra vulgatae editionis Sixti Quinti. (Antwerp, 1628). Balthasar I Moretus was a brilliant scholar who studied under Justus Lipsius while also working for the family business. When his brother Jan died, he formed a partnership with the printer Jan van Meurs, which ended shortly after this Bible was published. At the same time, his brother Jan’s wife Maria de Sweert was involved in the family business. This bible was bound long after it was printed. The spine of the beautiful goatskin binding is tooled in gold with a pomegranate motif.

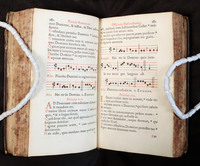

Rituale Romanum. (Antwerp, 1652). Religious texts continued to form the core of the Press’s output under Balthasar II Moretus in the mid seventeenth century. Although these books were printed in the tens of thousands, very few survive: only eight other copies of this 1652 missal are identified, and McMaster is the only North American institution to hold a copy. The text of two Psalms are printed in red and black on these pages, along with the musical notes for antiphons (short chants sung as refrains), recited during the Office of the Dead.

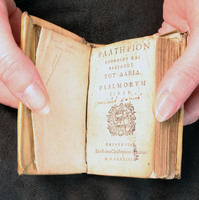

ΨAΛTHPION ΠPOΦHTOϒ. (Antwerp, 1584). This small 24o-format edition of the Psalms in Greek was modestly priced at 3 1/2 stuivers when it was first published in 1584. The tiny book has passed through the hands of many owners. It once belonged to a “Miss K. Macdonald” of Hamilton, Ontario — her inscription is visible on verso of the flyleaf. Several centuries earlier, a certain Jacob inscribed his name in Latin on the verso of the final printed leaf. Another owner, in a different hand, has written the price — “coustat 6 stuiferis” — on the endleaves.

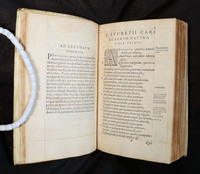

Lucretius. De rerum natura libri sex. (Antwerp, 1566). A portable edition of Lucretius’ “Nature of Things” — a lengthy metaphysical poem, originally written in the first century BCE, which sought to explore the phenomenon of existence through themes of atomism and impermanence. The work found generations of eager new readers in the increasingly inquisitive intellectual milieu of Early Modernity and was a focus of intense editorial activity. This edition boasts that it was “freed from innumerable errors” by the German-Dutch humanist Hubert van Giffen.

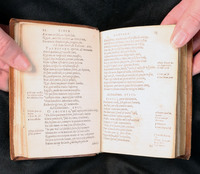

Catullus, Tibullus, Propertius. (Antwerp, 1569). This work gathers the output of three eminent Roman poets, active during the late Republic and early Augustan age, for a burgeoning commercial audience of early modern Latinists. Pride of billing is given to Gaius Verus Catullus, whose highly expressive and deeply personal oeuvre continues to be widely read by learners of Latin today. At left, we see his scathingly — and famously — obscene 16th poem. The word irrumabo (which cannot decently be translated here) is erroneously given as inrumabo.

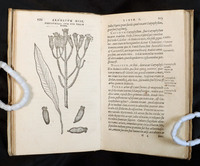

Garcia de Orta. Aromatum, et simplicium…apud Indos nascentium historia. (Antwerp, 1567). First Latin abridgement of Garcia de Orta’s Colóquios dos…medicinais da Índia, first published in Goa in 1563. Garcia, who spent most of his career in India, is best known for this work outlining the medical properties of Indian spices — like the cloves shown here — and their applications in treating tropical diseases. Its comparatively rapid dissemination in Latin, via Plantin’s press in Antwerp, speaks to the interconnectedness and extent of the Iberian political-intellectual sphere in the sixteenth century.

Benjamin of Tudela | Benito Arias Montano. Itinerarium Beniamini Tudelensis. (Antwerp, 1575). Benjamin of Tudela, a Jewish traveller born in twelfth-century Navarre, undertook an extensive journey circumnavigating much of the Mediterranean beginning in 1165. His account of the voyage contains a wealth of geographical and ethnographic information reflected in no other source. It was rendered from Hebrew into Latin by the great Spanish scholar-priest Benito Arias Montano, who first encountered the work while serving as an envoy to the Council of Trent.

Apuleius. Opera omnia… (Leiden, 1588). Apuleius, a Latin writer of Berber origin active in the second century CE, is best remembered for his Metamorphoses. This phantasmagorical — and frequently lewd — picaresque novel reflects the vivid inner life of its author, whose real-life adventures included running his own legal defense in a lengthy court case prompted by allegations that he had employed sorcerous means to seduce a wealthy widow. This complete edition of his works was published in Leiden under the supervision of Plantin’s son-in-law Franciscus Raphelengius.

Lucan. Pharsalia… (Antwerp, 1592). The Pharsalia, Lucan’s epic poem on the horrors of civil war, has an enduring resonance for societies wracked by strife. Antwerp, the base of the Plantin enterprise, was one such, serving as a flashpoint in the Eighty Years’ War between Spain and the emergent polities of the Netherlands. During the brutal sack of the city during the “Spanish Fury” of 1576, Plantin was obliged to offer repeated bribes in order to prevent the destruction of his business and home.

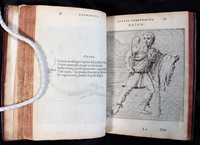

Justus Lipsius. Saturnalium sermonum libri duo… (Antwerp, 1598). Justus Lipsius, one of the great sixteenth-century humanists of the Low Countries, possessed a boundless fascination for the cultural heritage of Classical Antiquity. This original work focuses on the ancient Roman winter festival of Saturnalia, which was closely associated with the gladiatorial munera — sacrificial games in honour of Saturn in his role as god of the dead. This illustration depicts gladiatorial combat in a funerary context.

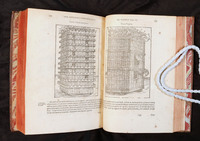

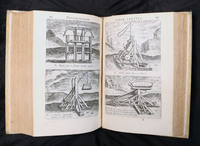

Vegetius. De re militari libri. (Leiden, 1607). Publius Vegetius Renatus, an obscure figure active in the late fourth century CE, is most famous for his De re Militari — a detailed treatise on military organization in late Antiquity. This edition includes commentaries by Godescalcus Stewechius, a noteworthy Dutch humanist, here supplemented by illustrations of enormous siege towers. These conveyances were intended to assist soldiers in surmounting fortified walls. The tower at right incorporates a battering ram.

Justus Lipsius. Poliorceticon … (Antwerp, 1614). This engraved illustration, from the Poliorceticon of Lipsius, depicts a fearsome array of heavy siege machinery. The work situates itself in the ancient Byzantine tradition of Poliorcetica — a genre encompassing manuals of siege warfare — and is bound with the author’s Five books on the Roman Army. Note the intriguing use of the Greek letter omega to represent the third “o” in “Poliorceticon.” This edition was published by Plantin’s daughter Martina and her son, Jan II Moretus.

This exhibit was curated by Ruth-Ellen St. Onge and Myron Groover in the spring of 2025.