Part Three: The New Beloved

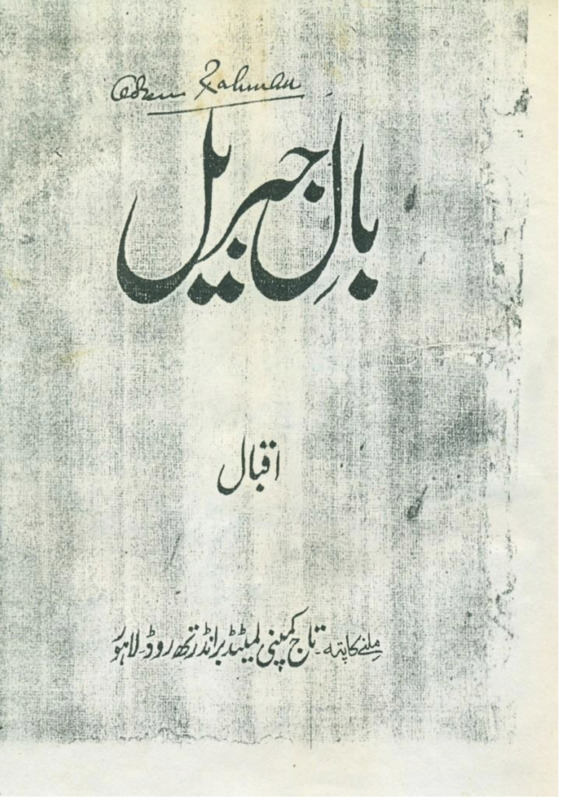

The 20th century dawned in blood and broadsheet. Across the world no honourable man of means could be simply concerned with his own advancement. No, now was the time of nations, when communities of faith and tongue began to bind themselves together with the toots of mass media, and express themselves with voices that shook even the colonies. The impact of this trend in Europe is well known, a World War, but it is under the shadow of this great conflagration that the first embers of Muslim nationalism would spark. The scene had been set for years, as the new Shahr Ashob brought the people the mourning of the past, and the mass Urdu literacy and european style papers encouraged by the Aligarh movement ensured even the lower classes could read it. A generation of neew intelligensia had been educated in European ways, and upon seeing the hypocrisy of the European yoke, grew tired of quietism. The kindling was lit as British troops advanced upon the Ottoman Empire, ruled by the ostensible Caliph of Islam, the highest religious authority for the Sunni muslims who made up the broadest fraction of Indian Islam. Long the Sick man of Euope, the Ottomans were the only ostensible Islamic great power left, the only source of emulation for young nationalists looking for a source of inspiration. The call of Jihad went up against British imperialists, but the true work of what would be called the Khalifat Movement would be done after the possibility of armed resistance had long since passed. Instead it would be conducted in mass protests for the retention of the Caliphate, organized by newspaper poets like the brothers Shaukat Ali and Mohammad Ali Jouhar revitalized the old poetic toolbox for a broad audience, coding revolutionary sentiment in the oblique metaphor so despised by Aligarh reformers. Their efforts would come to naught in the short term, as the last Caliph was overthrown not just by force of Entente arms, but by the disgust of his own people. In the long term however, they had lit a fire which could not be extinguished, young Muslim intelligensia with a pathway to the people and stomachs which hungered for freedom after 2 centuries of humiliation. The most famous of the movements Alumni, one Muhummad Iqbal, would best articulate these desires, turning his western education and Islamic upbringing to the works of poetry which would earn him the title "The Bard of The East". In his work he would develop the antecendents of modern decolonial theory. Neither the materialist reason of the Aligarh movement and their European masters, nor the blind traditionalists that sought to ignore the modern era could provide answers. To truly know freedom, Muslims must develop a new synthesis that returned to the revolutionary spirit of Islam, casting aside false and outdated cultural traditions while not becoming mired in blind materialism. A Muslim life could not be lived outside of a Muslim society, free from outside domination, whether political, economic, or cultural, whether British or Hindu.. So was born the Pakistan movement, the creation of a new state explicitly built on modernized Islamic law for modern Indian Muslims. There was a new beloved, and she was pure Islam, and she was the Nation, and she was the People, and she was all at once. And through verse and effort, she could be wooed. Though Iqbal would not live to see it, the generations of poets that would follow in the footsteps of Mufakkir-e-Pakistan have not given up their pursuit.