Unveiling Assyria's Artistic Legacy

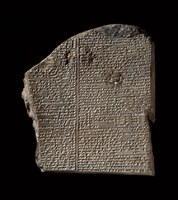

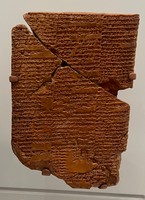

Throughout the lifespan of great civilizations, the love for storytelling has prevailed through the exploration of the arts. The Mesopotamians were no strangers to the arts of paintings, music, mythology, relief sculptures and cuneiform; anything to express the vast greatness of their empire, which they mastered and pioneered. A picture really is worth a thousand words especially for the Assyrians who established the Near East as their canvas. Wall paintings emerge that covered palace walls depicting great scenes of battles, with the kings at the front of the action. Accompanying the prideful paintings in the palaces were massive sculptures that symbolize protection, commonly carved from single slabs of limestone or alabaster. With the Assyrian empire and neighbouring Mesopotamian empires, the extraordinary corpus of written documents had taken the early world by storm. A form of storytelling that the Assyrians excelled in, their interests in literature birthed some of the best works in mythology and when the Assyrians weren’t telling stories, literature was used to document laws, transactions, and everyday life. No great empire is complete without the art of music, an artistic expression which the Assyrians enjoyed not only as a delight but specifically for religious purposes. Assyrians worshiped their gods through sacred hymns that accompanied great instruments which included drums, harps, cymbals, and flutes, and many more. Alongside great painters, sculptors, writers, builders and even musicians that the ancient Assyrian civilization birthed, leaves behind a cultural legacy and power of a great civilization.

The powerful, sublime aesthetic charge of ancient Assyrian art thus uniquely suffuses the English matrix of reception. Assyria’s sheer aesthetic appeal could even affect those acquainted (but not blindered) with classical canon. But this appeal, this model of the affective, sublime quality of Assyrian artifacts, was only one of the ways that was found to recommend Assyria as art. The aestheticization of Assyrian artifacts spans a wide range of positions and is employed in a variety of systems (Bohrer 2003, 157)