The beginning of Warburg's art historian career: the doctoral thesis on Botticelli

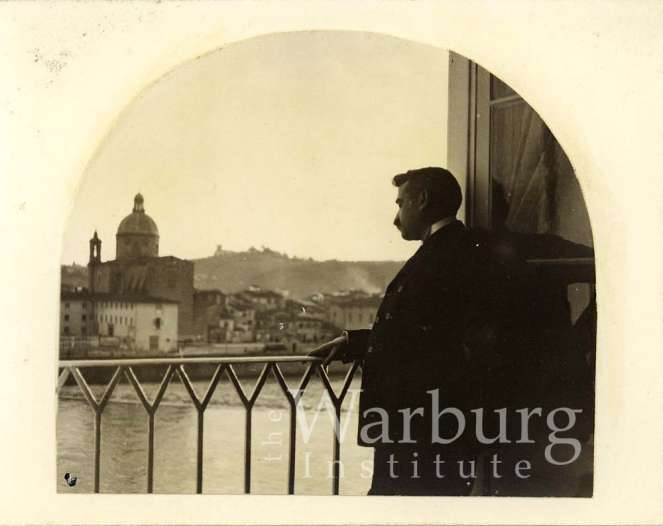

Warburg's photo 1894

This photograph was taken in 1894, a year after Warburg completed and published his doctoral thesis. In this photograph, he stands in his apartment in Florence overlooking the Arno River and the Church of San Frediano. At that time, he travelled to the Institute of Art History in Florence to further the iconographic research he had summarised from his Botticelli studies.

1894_Warburg in Florence copy.jpg © Warburg Institute (https://warburg.sas.ac.uk/archive/archive-collections/verknüpfungszwang-exhibition/aby-warburg-life-photographs), CC BY-NC 3.0 DEED

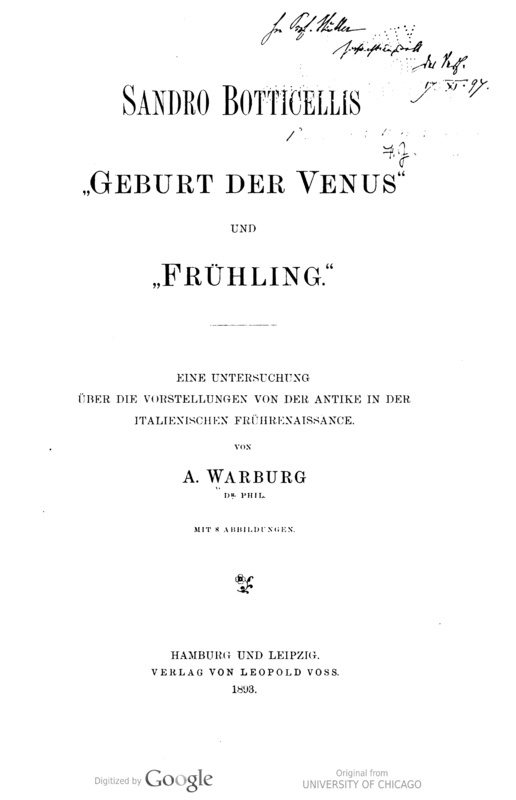

Warburg's Doctoral Thesis

This is the cover of Warburg's doctoral thesis. Prior to him, German understanding of Renaissance art came primarily from Johann Joachim Winckelmann, who believed that the kind of classical beauty revived by the Renaissance was characterized by quiet solemnity. Warburg, however, found that what the Renaissance Florentine artist Botticelli inherited from classical sculpture was dynamic, billowing clothing. This prompted him to ask the question that would later run through his life: what did the classical era mean? This thesis ultimately presents the exact opposite of Winckelmann's view, in which Warburg argues that the Renaissance inherited precisely the Classical period's appreciation of beautiful and intense movement.

chi.10686152-seq_9.jpg © HithiTrust (https://hdl.handle.net/2027/chi.10686152?urlappend=%3Bseq=9%3Bownerid=13510798903373238-13), Open Access, Google-digitized.

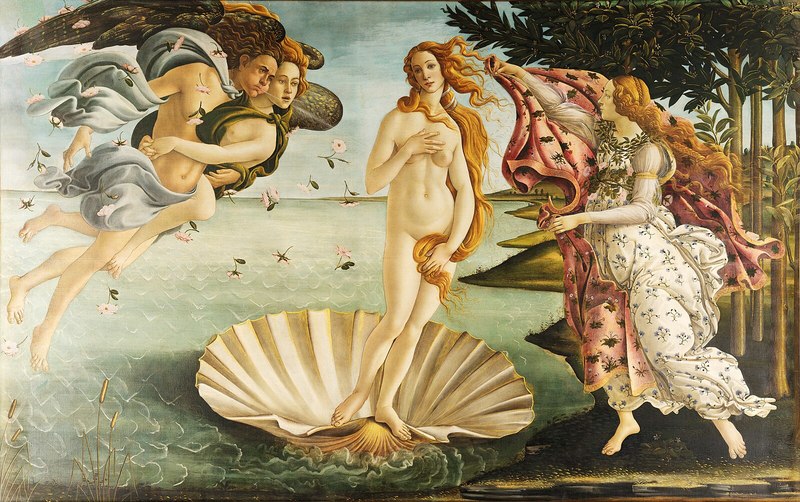

Botticelli: The Birth of Venus & Primavera

These two paintings by Sandro Botticelli, Birth of Venus and Primavera, are the subject of Valborg's study. Warburg found such depictions of dynamic ripples to be precisely what Botticelli had learnt from classical marble statues. Thus, contrary to the prevailing notion that for Renaissance artists the Classical meant only static solemnity, Warburg proved that the passion of movement was the Italian Renaissance imagination of the Classical.

Sandro Botticelli, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

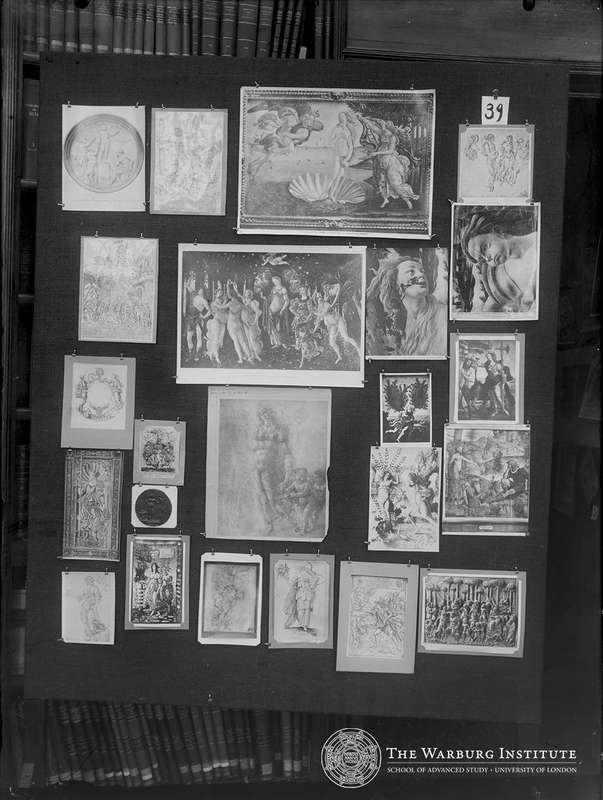

Botticelli in Warburg's Altas

This is part of the legacy of Valborg's final project at the end of his life. It is a testament to the fact that Botticelli studies undertaken at the very beginning of his art historical career occupied a very important place throughout his career. In his later studies of pagan beliefs and others, the question "What does classical mean?" This question has always occupied an archetypal position.

bilderatlas Panel 39.jpg © Warburg Institute (https://warburg.sas.ac.uk/archive/bilderatlas-mnemosyne/final-version), Public Domain