D.B. Riazanov and the Marx-Engels Institute (1900s-1930s)

David Riazanov, the idiosyncratic Russian Marxist, was on his second stay in exile – a common experience for many members of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party during the Tsarist era – when he was introduced by August Bebel to Engels’ papers in the SPD’s archive. He got to work almost immediately, organizing the archive, reclaiming papers that had been kept in the houses of members, and turning the party’s archive into a resource. It was Riazanov who went to Paris for the SPD to collect Marx’s papers in accordance with Laura Marx’s will. Riazanov had become the steward of these records and had transformed them from a mishandled accumulation of papers into an archive, yet still in 1917 he put down this work to return to Russia and participate in the revolutions of that year. But he couldn’t stay away for long.

Riazanov’s noted nonconformity didn’t serve him well in the early years of the revolution, despite the widespread acclaim he received for his knowledge of Marx’s theories, he was pushed aside as a party member in the early 20s. This didn’t seem to phase him much however, as it offered him an opportunity to return to what he’d fallen in love with, archival work. He founded the Marx-Engels institute in Moscow 1919 and immediately set to work establishing a network among his friends in Germany to have Marx and Engels’ archive shipped to him in photocopied form. These photocopies would be the basis for the first collected works of Marx and Engels.

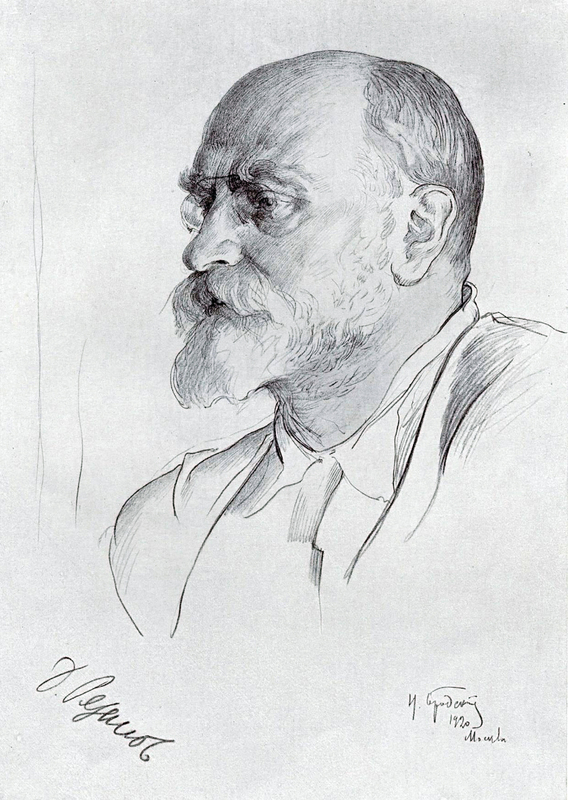

David Riazanov – variously spelled Ryazanov or Riazanov – was a Russian Marxist, activist, and writer before the October revolution that created the Soviet Union. Born in Odessa, his path in life intersected with a number of prominent figures in the Russian Marxist canon. Joining the Narodniks early in life, he would eventually become a Marxist on his first exile abroad, where he also met the ‘Father of Russian Marxism’ Georgi Plekhanov. After returning to Russia in the early 1890s, he was arrested and imprisoned until 1900. As the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party began to struggle with sectional infighting in the early 1900s, he took his own position, outside of the Bolshevik/Menshevik divide, starting a pattern he would continue into the early Soviet state, a “dictatorship mitigated by Riazanov,” as Lenin described it.

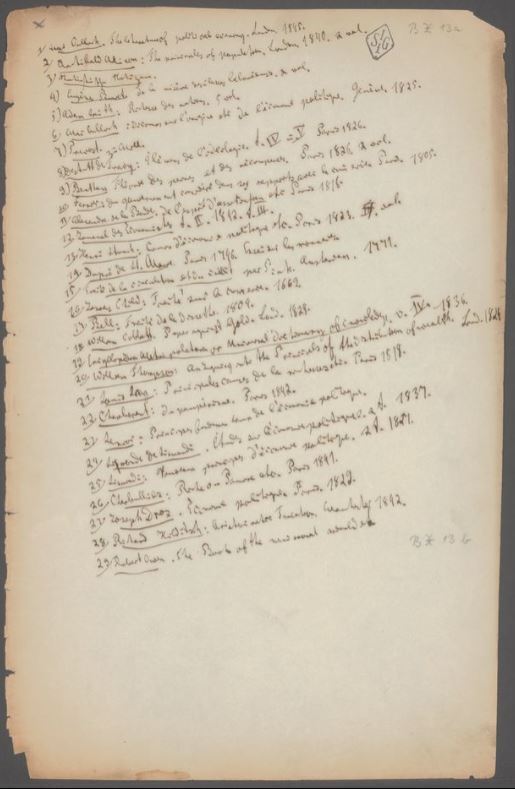

This manuscript is the first section of what would go on to be published as Marx’s Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844. These manuscripts went unpublished for more than 80 years and only came to light thanks to the work of the Marx-Engels institute under the direction of David Riazanov. The document is held today in the Archive of the International Institute of Social History (IISH), meaning it was likely sent to Moscow through Riazanov’s photocopying network. The network involved his friends at the Institute for Social Research (more famously known as the Frankfurt School) travelling to the archives in Berlin, photocopying documents, and having them transported to Moscow.

The 1844 manuscripts have proven hugely influential in the intellectual development of Marxism from their original publication to the present. The section on alientation in particular has proven a critical component of the Marxist Humanist perspective.

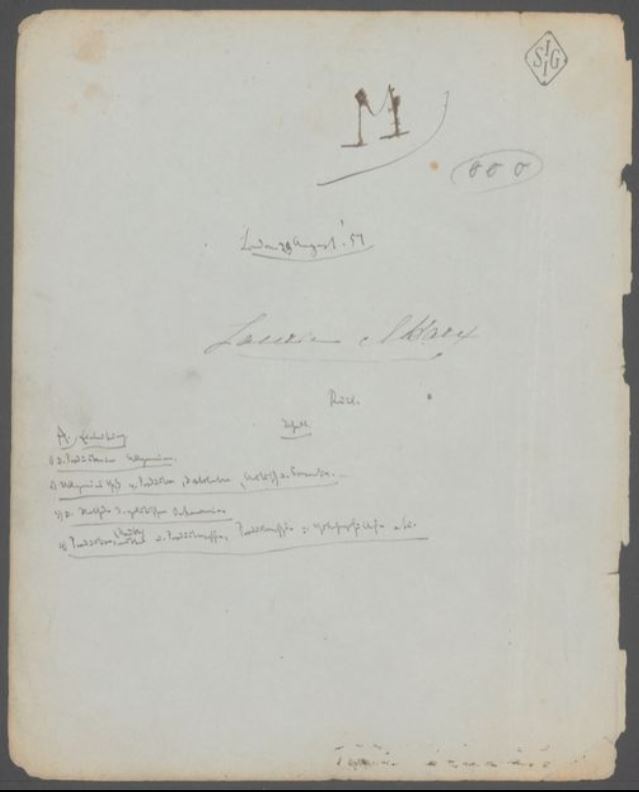

This short section of manuscript is a small part of what would later become The Grundrisse. Originally written as preparatory notes while Marx was beginning the period of study that would lead to the creation of Capital, the name Grundrisse literally translates to floor plans. The manuscript, contained in various sections at the IISH, followed a similar path to the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844. Unpublished for years, it was ‘rediscovered’ by the Marx-Engels institute under Riazanov and likely sent via the same path to Moscow. Unlike the 1844 manuscripts however, the Marx-Engels Institute would not be the ones to publish the Grundrisse; instead it would be published by the institution’s successor, the Marx-Engels-Lenin institute, a successor that came to be under unfortunate circumstances.

Riazanov was removed from his position as the head of the Marx-Engels Institute and arrested in 1931. Though he survived this arrest and lived his next seven years as a librarian, he was arrested again in 1938. Riazanov’s fate after his second arrest is uncertain, though whatever happened to him did eventually lead to his death. The Marx-Engels Institute did not survive his departure in 1931 for very long, reorganized as the Marx-Engels-Lenin institute, the work of the first MEGA would be abandoned, at least until the Institute’s later successor took up the task again.