Crisis, collapse, and survival (1989-Present)

The three years from 1989-1992 were not a good time to be employed by the ruling parties of East Germany or the Soviet Union. Nearly miraculously however, the MEGA2 would survive the collapse of the two states that funded it and the loss of the majority of their team in the aftermath of that collapse.

While it didn’t take much foresight for the East German team to reach out to the few contacts they had west of the Iron Curtain in 1989, it is probably the only reason the MEGA2 exists today. It’s likely similarly lucky that the International Institute of Social History (IISH) and Karl-Marx-Haus Museum responded so quickly, because by the next year, Germany would be reunified, and the MEGA project would be in serious jeopardy.

Together with the two institutes of Marxism-Leninism in Moscow and Berlin, the IISH and Karl-Marx-Haus created a plan to revamp and save the MEGA project. Together they created the International Marx-Engels Foundation, a new governing body for the project. The first goal of the Foundation would be to secure funding to keep the team in East Germany employed through German reunification, something they accomplished in part with the direct approval of then Chancellor Helmut Kohl. They also established stricter editorial standards, helping secure the legitimacy of the project and eventually European Union funding. These alternative funding sources would prove even more important as the Soviet Union’s collapse jeopardized another team of researchers.

This small section of notes from Karl Marx is, by most accounts, unremarkable. It consists of a few notes on different texts that he wrote around the year 1844, none of which have made a huge impact on the study of Marx or on history. Their significance lies mostly in their publication, as they made up a small section of the first MEGA volume to be published after the long crisis of the 1990s. They represent a huge accomplishment in the continuation of an intellectual project whose impact cannot be overstated. This section also demonstrates the project's ongoing commitment to a principle of completeness, seeking to publish all of Marx and Engels’ work to create a resource for future generations of scholars across the world. They arrived in print in 2002.

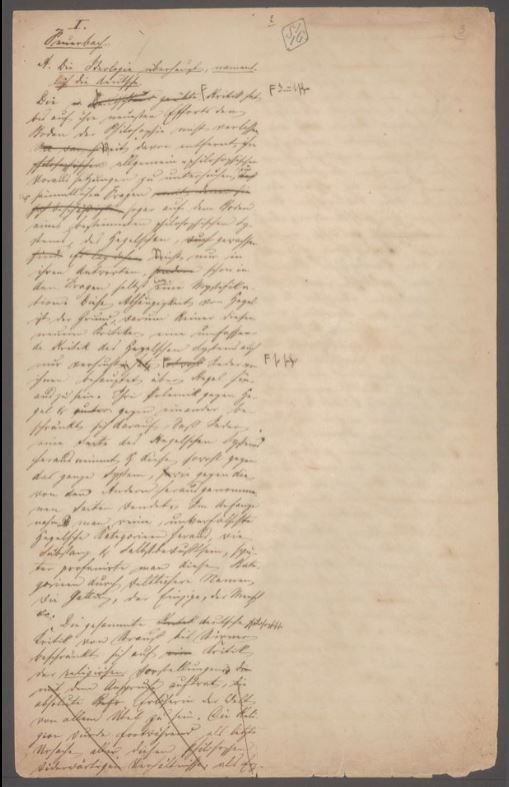

The above two documents are two different versions of the same work. The first document is the first section of the manuscript for one of Marx and Engels first major collaborations, what has come to be known as The German Ideology. The manuscript written between 1845-1846 went unpublished until the MEGA1 published it in 1932. The second document is a small selection of pages from a modern reprinting of the text based on this original 1932 edition. The versions of the book based on the 1932 printing all lack a peculiar quality present in the original draft manuscript: each page is divided in two, with Engels’ draft on the left side of the page and room for Marx and Engels to both comment on the right. Evidence of this process was excluded from the original MEGA1 printing of the manuscript, which as a stylistic choice is understandable. Yet the MEGA1 misses some important context and content from the discussions between Marx and Engels. While these notes are small, only appearing on some pages of the manuscript, they were included in a test printing of the MEGA2 in 2003, which was intended to demonstrate its new editorial principles. The small inclusion was enough for at least one academic who studies Marx and Engels to argue that the notes contained a fundamental disagreement between the two. These debates demonstrate the continued relevance of the value of completeness towards which the MEGA2 strives.

The ongoing work of the Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe and the history of collecting the totality of Marx and Engels’ life’s work demonstrates in a powerful way the tensions at the heart of the many political projects that emerged in the two men’s wake. The tensions between Marx’s clear trust in Engels to steward his intellectual legacy and the distrust of many modern “Marxists” in Engels’ work. The tensions between the incomplete and fragmentary nature of much of Marx’s work – as was demonstrated by the state of many of his Manuscripts — and the attempts by many to adhere to the man’s every word. The tension between studying Marx as an academic pursuit and using his work in political pursuits that nearly doomed the MEGA2. These tensions will not be resolved by collecting Marx and Engels’ work, some may even be aggravated. Yet, the devotion of scholars and activists across over a century lives on today in the continuation of this project towards its ultimate goal: to leave, as a resource to future generations, the full corpus of contradictory, revelatory, and important work of these two long dead men.