The Correspondence with Chatelaine

In October 1952 Judith Robinson began working freelance for Chatelaine. In February 1953, the magazine’s head editor sent her a letter saying “I realize now that our arrangement had little chance to survive”. The collection of letters in Robinson’s archive tracks a working relationship as it deteriorates, revealing the gulf between what Chatelaine wanted and what Robinson wanted to deliver.

Chatelaine’s head editor, John Clare, was excited to have Robinson come write for them, and from his letters he appears to be a personal friend. He was “fine” with the first column she submits (“Progress and Mashed Potatoes”), and it is Clare who suggested that she do “the occasional narrative”. This is followed by more personal letters, including one where Clare claims he will handle her articles with the utmost respect, and not interfere even in things she’s told him he can edit freely. But in that same letter he reiterates that he wants her to branch out into more entertainment as a “change of pace” for “les girls”. Even when things are going as good as they get for this partnership, there is some nudging to get Robinson to do what Clare is looking for. Looking at the few letters we have from the editor of the Telegram, the newspaper Robinson began working at in mid-February 1953 immediately after breaking things off with Chatelaine, we see editor J. D. MacFarlane using a lot of the same handling tactics that Clare was employing in his November letters: pairing gentle criticism with heavy doses of flattery.

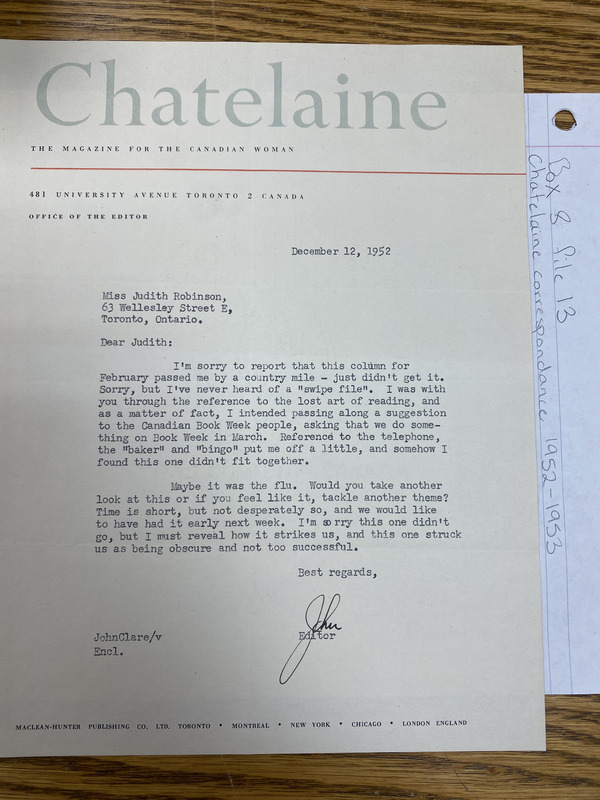

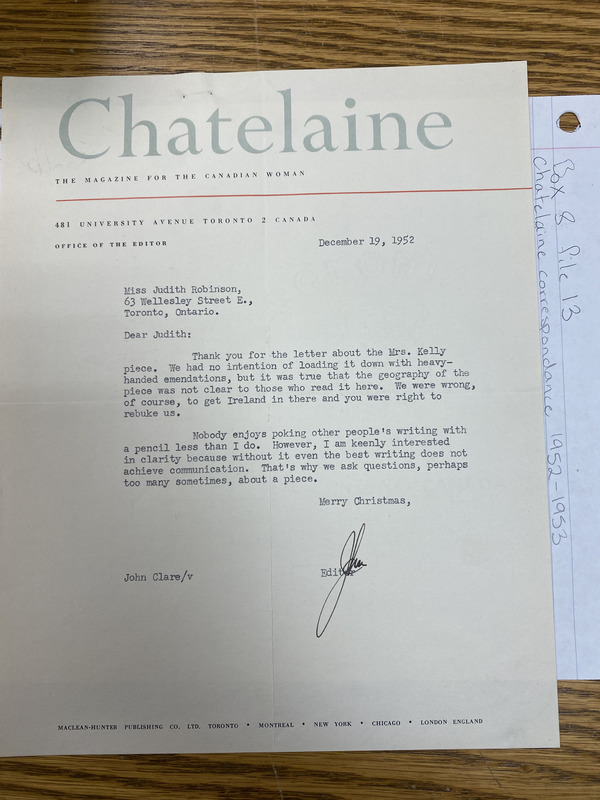

December is when the catalyst for the end of this relationship emerges. Robinson submits an article that Clare says he “just didn’t get.” He asks for an alternative, to which Robinson takes his suggestion for a short narrative and submits a draft of “Mrs. Kelly’s Lily.” Clare criticizes that one too, saying it needs more clarification. This is where it all blows up. Robinson strikes back in a letter of her own, citing all the places in the draft where she (in her eyes) had already made things clear, suggesting that perhaps her sophisticated allusions simply went over the heads of the editorial staff. Clare responds with an apology. After this, correspondence dramatically decreases. The only letter Clare sends in January is a guideline for what the special June issue on Elizabeth II’s coronation will focus on.

The February 10th letter is when Clare vents his anger and the relationship officially falls apart. In response to Clare’s previous apology, Robinson submitted an article criticizing meddling and ungrateful editors. Clare sends this targeted diatribe back, and blames the situation on Robinson for getting so angry in the first place. “We could continue the discussion,” he writes in his last letter, “but there’s not much point to it.”

What we can say definitively is that both sides were unsatisfied with this partnership. Robinson was frustrated with the fact that the magazine kept nitpicking her content, and the magazine’s editors were frustrated at her unreasonable frustration and her shortcomings in delivering what they wanted. It’s clear in letters that Chatelaine’s editors (and readers) were not thrilled with what Robinson was producing: meandering and “obscure” pieces that weren’t offering the entertainment they wanted.

Why this disconnect existed is something we can only speculate towards. Why was Robinson so deeply offended by the editors’ criticism of her work? It could have to do with the personal nature of her relationship with John Clare; perhaps she expected him to understand exactly what she was doing in her drafts? Or maybe it was the buildup of a long career of editors trying to pin down her content, as Chris Long describes in his lecture on Robinson's archive.14 Valerie Korinek characterizes John Clare as reluctant and negligent in his handling of the magazine, and that may be true in other, but here we see him trying to direct Robinson into what he wants, showing a pretty clear vision for the magazine: one that's mainly entertainment focused.15 Maybe Robinson simply didn’t mesh well with the mandate to give readers a “change of pace” to keep their attention. Maybe she felt slighted because her narrative story submissions still weren’t received well. Maybe there was something happening in their personal relationship that soured the whole thing. Regardless, the behind-the-scenes correspondence during Robinson’s time at Chatelaine reveal a frustrating mismatch of expectations between writer and publisher.