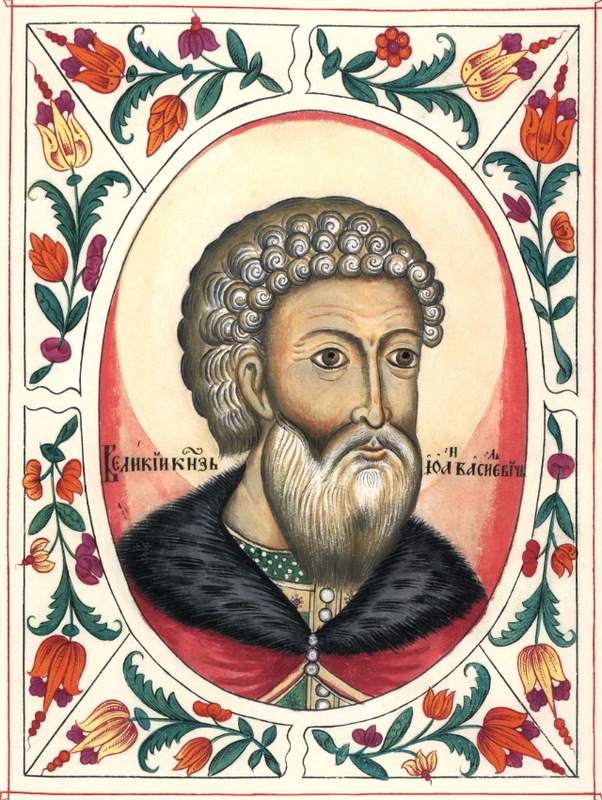

Ivan the III and Московское

The Rus were a branch of the Slavic people that were ruled by the descendants of Viking adventurers who settled in modern Ukraine and Western Russia. After emerging in the 9th century, they were at first antagonists to the Eastern Romans, famously launching a great siege on Constantinople in 860 CE. Relations between the two people would begin to warm with the conversion of Olga the Great to Eastern Orthodoxy in 957, who was impressed with the grandeur of the Empire and its great churches.

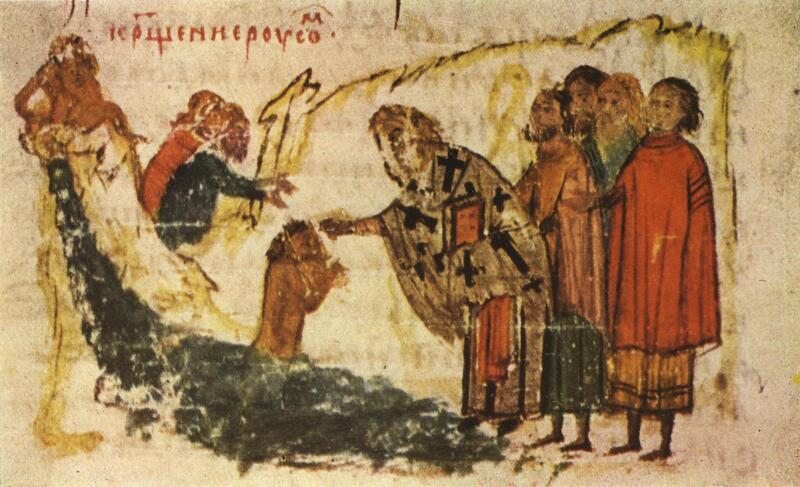

However, it was her grandson Vladimir who would forever tie the Kyivan Rus to the Eastern Romans. A pagan at birth, he either offered (or was offered) a deal in exchange for converting to Christianity and helping Emperor Basil II in a civil war. The hand of Basil’s sister, Anna. At the time, Anna was considered to be of the highest possible prestige for a royal marriage, a legitimate Roman princess. He accepted, and he was baptized in 989. From then on, relations between the two would be up and down, but the Rus remained tied to Byzantium through their Eastern Orthodox faith. In 1472, another great marriage would once again change the relationship between these two very different people. At this time, the unified Kyivan Rus of Vladimir’s day had been split, conquered, and vassalized by the Mongols, but the most powerful of the Rus states was Moscow.

This idea was based on both dynastic and religious grounds. Under the succession laws used by European nations of the time, Ivan’s wife and children had a claim to the imperial throne through their connection to the last Emperor. Beyond that, Moscow was now the greatest of the Orthodox nations left standing after the Ottoman conquests, and to them, this made them the natural successors of Byzantium. Ivan was the first to call himself a Tsar, the Slavic version of Caesar, which theoretically meant he was at the same level as an Emperor. The notion that they were successors of Byzantium was a powerful one, with church leaders like Philotheus of Pskov writing about it. The court rituals brought by Sophia, and the dress of the various Tsars also show this. The idea was still prominent in Russian circles all the way to the reign of Catherine the Great, who fully intended to restore the Eastern Roman Empire and put her son Konstantine on the throne. While she never managed to do so, Byzantine ritual and practise survived right up until the end of the Empire in 1917.

![By Unknown author - Site about Radzivill chronicle: [1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2795251](https://expo.mcmaster.ca/files/large/d88cfb3c1a190aaf8b7c6c2666a94dccb0eead6e.jpg)

![By Mikhail Nesterov - [1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=139257866](https://expo.mcmaster.ca/files/large/fd75f75e12106b8df83b67d300cba7aadacdeed9.jpg)